The fountain in the Carrés Saint-Louis

A new quarter in Versailles

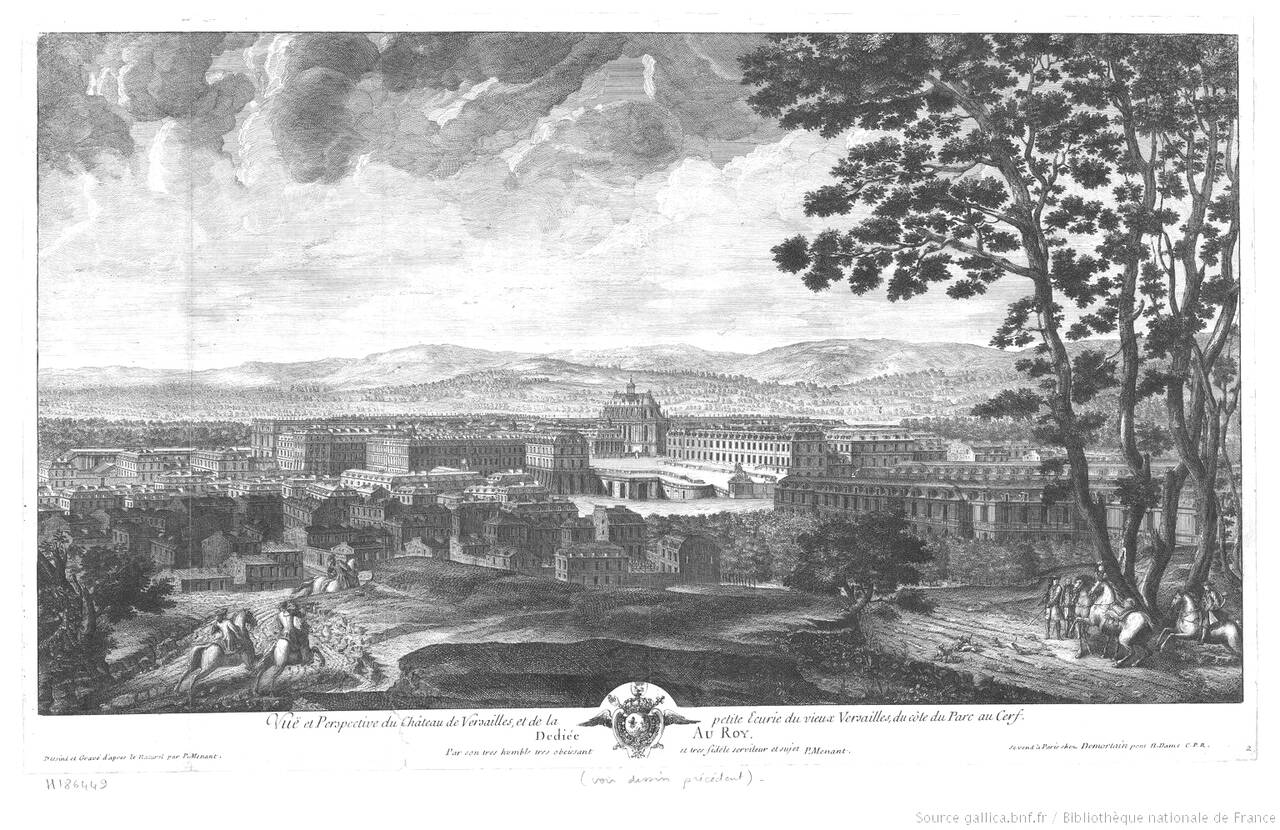

King Louis XIV, who wanted to develop his city southward, resigned himself to give up his “Deer Park” (game reserve) and built a whole new quarter next to the “Ville Neuve” quarter (now called the “Notre Dame” quarter). In this vast area, the King distributed to various “quality people” or faithful servants, as a reward, 473 plots of land on which they had the obligation to build.

In this context, two main roads, crossing each other, were to serve the future quarter: “Rue Royale” from South to North and “Rue d’Anjou” from West to East. At their intersection, a vast area was to be built, named “Place du Parc aux Cerfs” (Deer Park Square). A number of houses were gradually built, with an obligation to be “not too high” to avoid spoiling the view of the Palace, which had to be the tallest visual landmark.

The Carrés Saint-Louis

The houses, called “baraques” (“baraque” meant a single-storey building, unlike the type of grand townhouse or residential building that usually housed shops) had a ground floor opening onto the street, a slate roof, a cellar, a backroom with a fireplace and windows giving onto the centre of the square. They entirely enclosed the four Carrés located on either side of the crossroad formed by the two main roads, respectively dedicated to the sale of seafood (“Carré à la Marée”, later named “Carré au Puits”), meat (“Carré à la Boucherie”, later named “Carré à la Terre”), oats (“Carré à l’Avoine”, which kept its name, where horse feed was sold to private horse owners and for the King’s horses) and, lastly, fruit and vegetables (“Carré aux Herbes”, now known as the “Carré à La Fontaine”).

The quarter and its “baraques” (which were authorised to add a second storey) were developed later under the reign of King Louis XV.

A water reservoir to supply the quarter

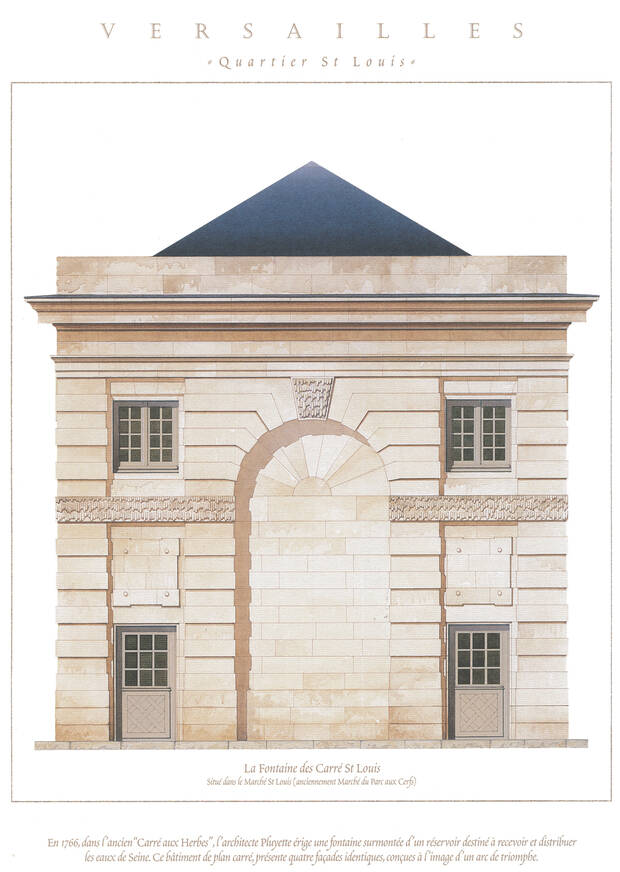

The “Carré à La Fontaine” derived its name from the reservoir built in 1766 by Pluyette, an architect and engineer. Like all reservoirs in those days, it served as a water supply in case of fire. Drained from the Saint-Quentin plateau (via an ingenious system of water channels), the water was carried via the Buc Aqueduct and stocked in the Gobert Ponds (near the drinking trough at the top of Avenue de Sceaux). From there, it ran by gravity to the first floor of the reservoir where it was stocked. It supplied four basins placed under the four arcades, used as drinking troughs for the animals. The building was in fact partly hollow, like the reservoirs near the Royal Opera House in rue des Réservoirs or those in rue Carnot.

The visible part of the building was an outer shell and, inside, the ground floor was an empty room in which pillars or arches supported the reservoir on the upper level. In the case of this reservoir, it seems that, rather than pillars, there was a robust floor with large, exposed beams that can still be seen.

An unusual architectural design

The currently existing external windows and doors are completely different from those of the original façade: there were many less as they served no use. The building was just a technical building, not intended for residential use. There was a single door on the south side (in one piece, contrary to the current stable-type door with two horizontal panels) and the attic windows were just openings hidden by wooden shutters.

The current joinery, patio doors and rectangular windows are in fact pastiches of the 18th century, entirely redesigned by the architect Jean-Claude Rochette in the late 1960’s, when the building was converted into offices for the architects and the housing department of the City of Versailles (until a few years ago). The internal reservoir was demolished so that offices could be installed on the first floor.